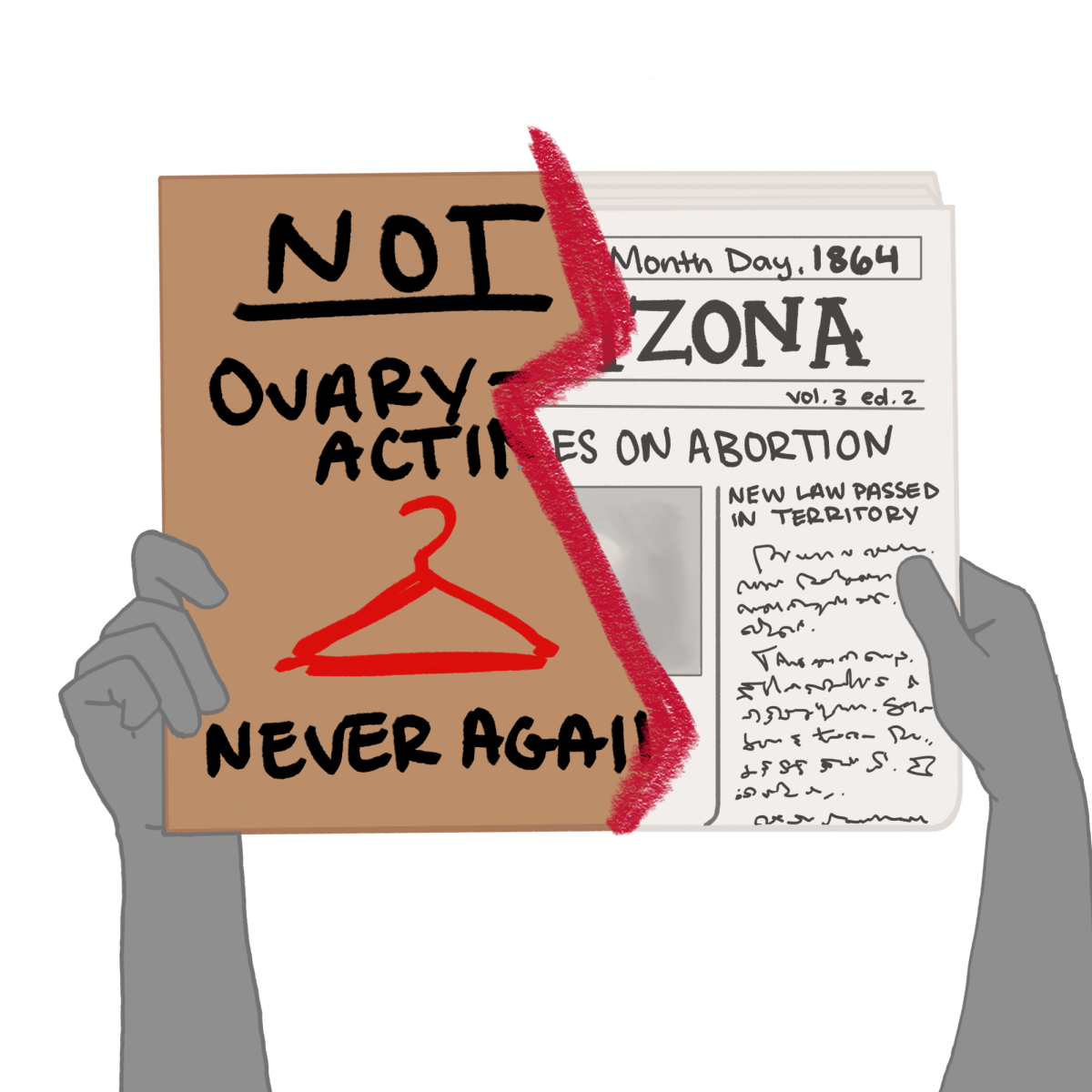

Reproductive rights: In the United States, the debate typically focuses on the choice whether or not to have children. For citizens of the People’s Republic of China, it’s the other way around.

Beginning in 1979, the Chinese government imposed a law restricting parents to just one child per household. Just recently it has increased that number to two.

It is not difficult to imagine the objections to any version of this law in the United States; enforcement would be impossible, requiring either that children be taken from their parents or that parents be sterilized after having their first child.

Furthermore, the eugenic aspect of government control of the gene pool also poses a serious ethical question. In consideration of this, the one child rule seems a violation, or at least a severe imposition upon, the rights of the individual.

What could justify such a rule, difficult to enforce and ethically questionable at best? Perhaps the problem of over population.

Many of the environmental problems facing the human race are exacerbated by an overabundance of human life. The increase of the human population has caused, and will continue to cause, food and water shortages, increases in pollution from traffic, industry and energy production, as well as the destruction of vital ecosystems to make room for human settlement.

But does the threat, even if certain, of global environmental change and the negative impact it promises justify the suspension of reproductive rights? If so, what others might be? And if not, what should be done to address this contemporary tragedy of the commons?

The authoritarian communist government of China is not alone in demanding individual sacrifice for the common good; the laissez-faire solution to the tragedy of the commons is also to take from individuals what might be considered a natural right; the right to a share of the common resources.

It does so through the imposition of property rights rather than the decree of the state, but property rights are enforced by the state.

It’s a complicated question—the answer to which comes down to the prioritization of individual freedom or collective good, or some third, unforeseen alternative likely in the form of a compromise. It is also possible that no change might be made to the current growth rate; however nature, unlike government, enforces its laws without exception or any regard for such abstractions as individual freedom or collective good.

The environment will respond to an overpopulation of humans the same way it responds to an overpopulation of deer; when the resources are used up, the excess will die off, mainly through starvation and the spread of disease.

With that said, in the end it isn’t ethical or environmental concerns that determined this policy change, but economic ones; an aging population simply cannot support the demand for manufactured goods, which, like the population, seems only to grow.